Running Shoes and Marathon Records

ANOTHER LOOK AT THE IMPORTANCE OF CUSHIONING

Kelvin Kiptum’s world record time of 2:00:35 at the Chicago Marathon on Sunday 10/08/23 is an outstanding athletic achievement and a testament to Kenya’s system for developing elite distance runners. A little more than a month later Ethiopian Tigst Assefa ran 2:11:53 at the Berlin Marathon (9/24/23), destroying the women's marathon record by more than 2 minutes. Even for people familiar with the years and sheer volume of dedicated work these athletes put in, Assefa and Kiptum’s achievements are incredible and well earned. Congratulations to both!

But what part, if any, did their shoes play? Popular opinion, stoked by the marketing machines of footwear giants, is that new and exotic materials return energy more efficiently than previous running shoes and account for this heroic feat. For a more in depth understanding of why this is not the case, please read our blog on the trampoline effect. However, nobody has described in technical detail just how these shoes work. Instead, the explanations all fall back on a causation fallacy by claiming the proof of the mechanism is the world record itself.

In other words, we have a theory and because the outcome was what we wanted, the theory must be correct. It is like assuming that the number of animals that are left at animal shelters are due to people not understanding how difficult it is having a pet. In reality, this could be one reason as could financial difficulty, personal circumstances etc.

But there is another plausible mechanism that isn’t being spun by the marketing giants: shock absorption.

Moses Tanui was the first to break 1-hour in the half marathon in 1993. Tanui sustained an average pace of 4:33 min/mile over the 13.1 mile course, slightly faster than Kiptum’s 2023 average marathon pace of 4:36 min/mile. Tanui’s traditional low-profile racing flats were very different from the high stack-height shoes worn by Kiptum, yet runners in Tanui’s era sustained those incredible paces for a half marathon. Tanui’s shoes were lightweight, but purported no energy advantage for the runner.

High stack-height shoes have one obvious difference from older racing flats: they’re very soft. A soft material with enough thickness so they don’t bottom out, absorbs more impact energy than a firm low-profile racing flat. The problem is that the marketing giants will have you believe that the new foam properties, perhaps aided in some way by carbon plates and spring-loaded cassettes, manage to return impact energy to help the runner move with less effort. Add up all those steps of slightly less effort and you have an energy savings that can be burned to run faster. The problem with this idea is that it violates the 2nd Law of Thermodynamics. In other words, it’s not physically possible.

The scientific literature is filled with descriptions of running as a bouncing motion where impact energy is temporarily stored in the tissues and then released, analogous to a bouncing ball. However, this is focussing the description of what happens to the leg that is on the ground (stance leg).

Universally, these bouncing gait descriptions omit the acceleration of the mass of the swing leg (i.e. not the leg that is in contact with the ground) and the muscles around the hips and in both legs in making a stride. It is essential to remember that the swing leg is being powered from the moment the support leg touches the ground – this is why you cannot move forward just by kicking your legs when they are both in the air. You need one stable foot to allow the other leg to move forward.

The swing leg continues to move forward and up during the entire time the opposite leg (stance leg) is in contact with the ground. The swing leg, being a substantial part of the whole body, moves the body (technically, it moves the center of mass of the body) forward and upward in a smooth, but complicated motion. To understand this further, think what happens when you walk – if your swing leg does not go past the stance leg, you cannot take the next step. The swing leg is needed to accelerate you forward.

The idea that energy being stored outside the body in the sole of a shoe can simultaneously make its way into the motion of the swing leg is, of course, absurd. The advocates of shoe energy return attempt to get around this issue by imagining the body as a rubber ball that moves as a whole rather than as a jointed muscle driven organism that moves its limbs.

In addition to this obvious definitional problem, the bouncing-energy-return idea omits internal friction. In the case of the foot in running, as soon as your foot hits the ground, friction is required to stop it sliding forward (think of trying to run normally on ice). Friction generates heat, which must be dissipated from the body. Omitting friction also violates the 2nd Law of Thermodynamics and reveals that the proposed bounce motion is implausible.

However, you must also activate your muscles and move your joints to help slow the movement and absorb the impact energy, which also generates energy. Compare running uphill to downhill. Uphill, you have to move against gravity and it takes a lot of energy due to the increased heart rate and effort to generate the power making you puff harder.

By contrast, when you run downhill, you do not need to generate as much power to move forward, as this is helped by gravity, but you need to use your muscles much more to resist the motion – this is why your muscles work harder downhill.

A plausible idea that is consistent with thermodynamics is that a thick soft shoe absorbs more of the impact energy, compared to a low-profile racing flat, so that less impact energy must be absorbed by the body. This is the commonsense understanding for cushioning in shoes. When the body has to do less work generating the friction force to halt the downward motion at impact, it experiences less fatigue.

Over the many steps of a marathon, less fatigue means that the legs can perform their function better. In other words, a big difference between 1993 racing flats and 2023 racing shoes is that modern shoes may reduce the cumulative fatigue in a runner. The fatigue notion contrasts with the energy notion by identifying a different limitation in the body than just propulsion energy. Since fatigue limits our legs ability to move properly, reducing fatigue is advantageous.

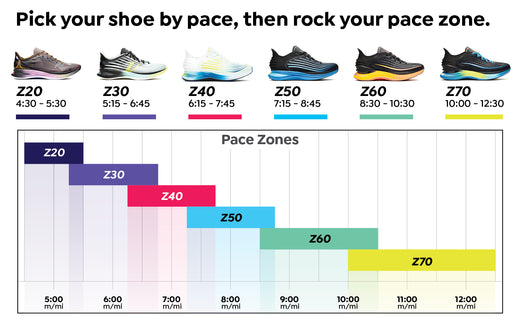

Decreasing impact shock absorption in a running shoe is the essence of Vimazi’s pace-tuned technology. Vimazi shoes are softer at impact so that your legs feel less stress. In a traditional shoe, because the material at the forefoot as it is at the heel, it allows the foot to continue moving towards the inside or medial aspect of the foot, potentially prolonging pronation and increasing muscular activity. Vimazi’s technology then combines the enhanced shock absorption with greater torsional stability in the forefoot to reduce this strain. Insert link to pronation blog (so will need to be up) and add in the new picture explanation.

Impact shock and push-off strain vary as a function of pace, and it’s a careful balancing act to get the tuning just right. With our patented tech, Vimazi running shoes relieve two sources of stress, not just one: the stress of continued pronation and the stress of impact shock. Together, you get the best combination for reduced fatigue and healthy, enjoyable running.

Impact shock and push-off strain vary as a function of pace, and it’s a careful balancing act to get the tuning just right. With our patented tech, Vimazi running shoes relieve two sources of stress, not just one: the stress of continued pronation and the stress of impact shock. Together, you get the best combination for reduced fatigue and healthy, enjoyable running.